Case Citation: AIR 1974 SC 555

Judges: A.N. Ray (CJI), D.G. Palekar, Y.V. Chandrachud, P.N. Bhagwati, V.R. Krishna Iyer

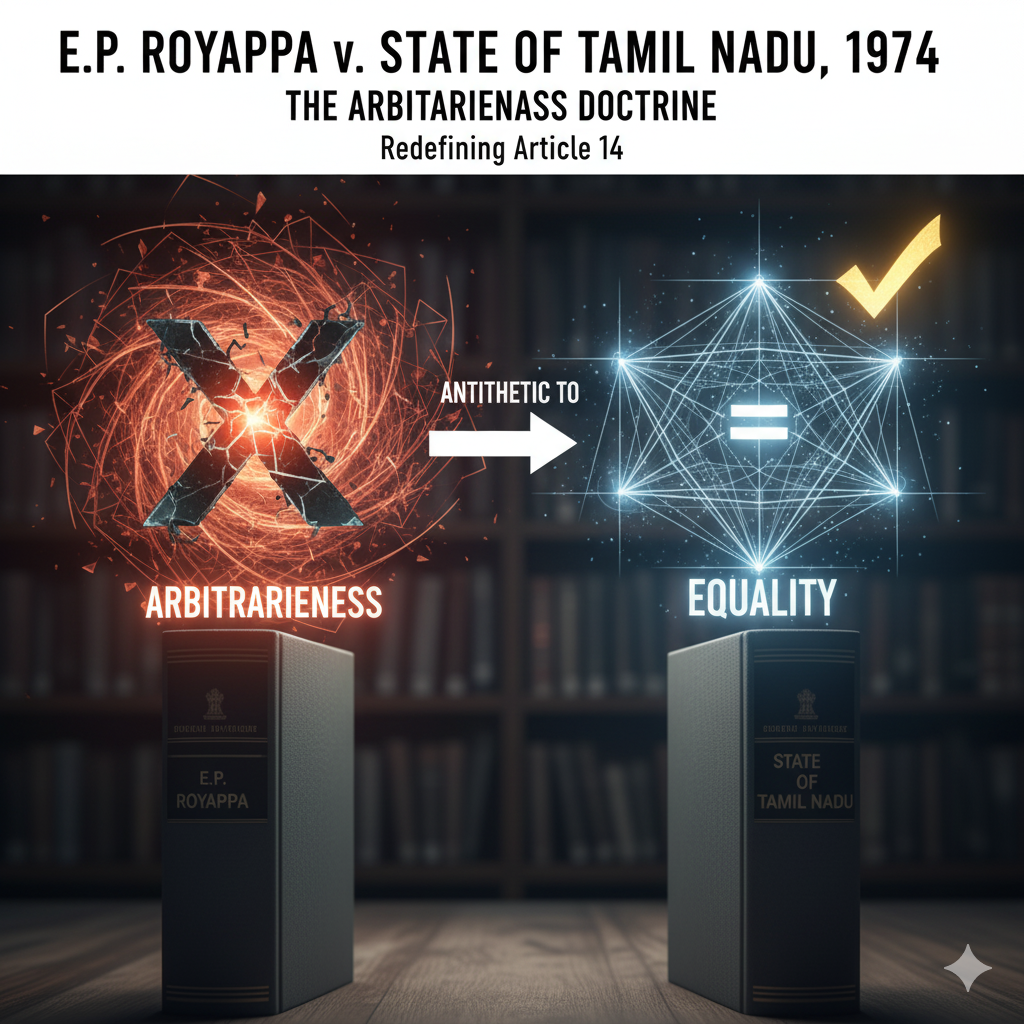

Core Principle: Introduced the “Arbitrariness Doctrine,” expanding the scope of Article 14 of the Indian Constitution.

Table of Contents

Toggle🏛️ Introduction: A New Test for Equality

In the landscape of Indian Constitutional Law, few cases stand as tall as E.P. Royappa. While the petitioner, Mr. Royappa, technically lost his case on the facts, the judgment delivered a profound legal principle that fundamentally changed how we understand the Right to Equality under Article 14.

This case is the origin of the “arbitrariness doctrine,” famously holding that equality is antithetic to arbitrariness. It moved the test for equality beyond the traditional “reasonable classification” and gave the judiciary a powerful tool to strike down administrative actions that were whimsical, capricious, or unreasonable.

Facts of the Case

- The Petitioner: Mr. E.P. Royappa was a senior IAS officer in the Tamil Nadu cadre. He held the prestigious post of Chief Secretary of the state.

- The Transfer (Part 1): The state government created a temporary post of “Deputy Chairman” in the State Planning Commission. Mr. Royappa was transferred from his post as Chief Secretary and appointed to this new post.

- The Transfer (Part 2): Shortly after, he was transferred again, this time to another newly created post: “Officer on Special Duty.”

- The Challenge: Mr. Royappa was aggrieved by these transfers. He filed a writ petition under Article 32 of the Constitution, challenging the government’s orders.

- The Allegation: He alleged that the transfers were not in the public interest but were an act of political vendetta and mala fides (bad faith) by the Chief Minister. He claimed the new posts were inferior in status and responsibility to the post of Chief Secretary, and the transfers were a disguised form of demotion and punishment.

📜 Issues Before the Court

The Supreme Court was faced with two primary questions:

- Question of Fact: Were the transfers of Mr. Royappa motivated by mala fides on the part of the Chief Minister?

- Question of Law: Were the posts of Deputy Chairman and Officer on Special Duty inferior in status and responsibility to the post of Chief Secretary? Did the transfers, therefore, violate Article 14 (Right to Equality) and Article 16 (Equality in public employment)?

🗣️ Arguments

- Petitioner (E.P. Royappa):

- The transfers were a classic case of political victimisation.

- The post of Chief Secretary is a “cadre” post, the highest in the state’s civil service, with immense administrative power.

- The newly created “non-cadre” posts were “created to accommodate” him and were merely “glorified” posts with no real power or responsibility.

- This amounted to a demotion without following the due process required under Article 311.

- The state’s action was arbitrary and hostile, thus violating the principle of equality under Articles 14 and 16.

- Respondent (State of Tamil Nadu):

- The allegations of mala fides were baseless and strongly denied.

- The transfers were made for administrative reasons and in the “exigencies of service.”

- The new posts were not inferior. The state argued that they carried the same pay scale, status, and responsibilities, and were, in fact, “posts of great importance.”

- Since the posts were equivalent, there was no demotion, and Articles 14, 16, or 311 were not violated.

⚖️ The Judgment: A Landmark Declaration

The judgment was delivered by a five-judge bench, but it is the concurring opinion of Justice P.N. Bhagwati (on behalf of himself, Chandrachud, and Krishna Iyer, JJ.) that became immortal.

1. On the Factual Issue (Mala Fides)

The Court (by majority) held that the petitioner, Mr. Royappa, failed to prove his allegations of mala fides. The burden of proof for mala fides is exceptionally high, and the court found the evidence insufficient to establish that the Chief Minister had acted out of personal malice.

The court also accepted the state’s argument that the new posts were equivalent in status and pay to the Chief Secretary. Therefore, Mr. Royappa lost his case on the facts.

2. On the Legal Issue (Article 14)

This is where the case made history. Justice Bhagwati, while agreeing with the majority’s conclusion on the facts, seized the opportunity to give a new, dynamic interpretation to Article 14.

He articulated the “New Doctrine of Equality” or the “Arbitrariness Doctrine.”

Key Principles from the Judgment:

- Equality is Dynamic: The court stated that equality is a “dynamic concept with many aspects and dimensions,” and it cannot be “cribbed, cabined and confined” within the old limits of the “reasonable classification” test.

- The Link with Arbitrariness: The judgment established for the first time that arbitrariness and equality are sworn enemies. Any action that is arbitrary is, by definition, unequal and unjust.

- The Famous Quote: Justice Bhagwati’s words became the locus classicus (the classic formulation) of this principle:

”Equality is antithetic to arbitrariness. In fact, equality and arbitrariness are sworn enemies; one belongs to the rule of law in a republic while the other, to the whim and caprice of an absolute monarch. … Where an act is arbitrary, it is implicit in it that it is unequal both according to political logic and constitutional law and is therefore violative of Article 14.“

Significance & Case Analysis

E.P. Royappa marked a profound shift in the interpretation of Article 14.

- Before Royappa (The Old Doctrine): The test for Article 14 was primarily the “Reasonable Classification” test (from State of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali Sarkar). To prove a violation, you had to show:

- That the law created two different groups (classification).

- That this classification was unreasonable and had no “intelligible differentia” (no logical basis).

- That there was no rational nexus between the classification and the law’s objective.

- After Royappa (The New Doctrine): The “Arbitrariness Doctrine” was added as a new and more potent test. Now, a state action (administrative or legislative) can be struck down as violating Article 14 even if it applies to everyone equally, simply because the action itself is arbitrary, unreasonable, whimsical, or capricious.

This case armed the judiciary with a powerful scalpel to review administrative discretion. It ensured that the government cannot act on a whim. This principle was further cemented and expanded in subsequent landmark cases like Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978), where the court held that any procedure established by law (Article 21) must be “right, just and fair” and not “arbitrary, fanciful or oppressive.”

Conclusion

E.P. Royappa v. State of Tamil Nadu is a testament to the fact that a case lost on facts can win a war for legal principle. It remains a cornerstone of Indian constitutional law, ensuring that equality is not just a formal concept but a substantive protection against the arbitrary exercise of state power.

- Dying declaration

- Bihar APO Exam Date 2026: Prelims Scheduled for July 15 – Check Official Notification

- UP APO Exam Date 2026 Announced: Check UPPSC Official Calendar & Schedule

- Indian Army JAG 124 Notification 2026: Vacancies, Eligibility, and Apply Online

- Official IBPS 2026-27 Calendar Out: Check SO Law & RRB Scale II Dates