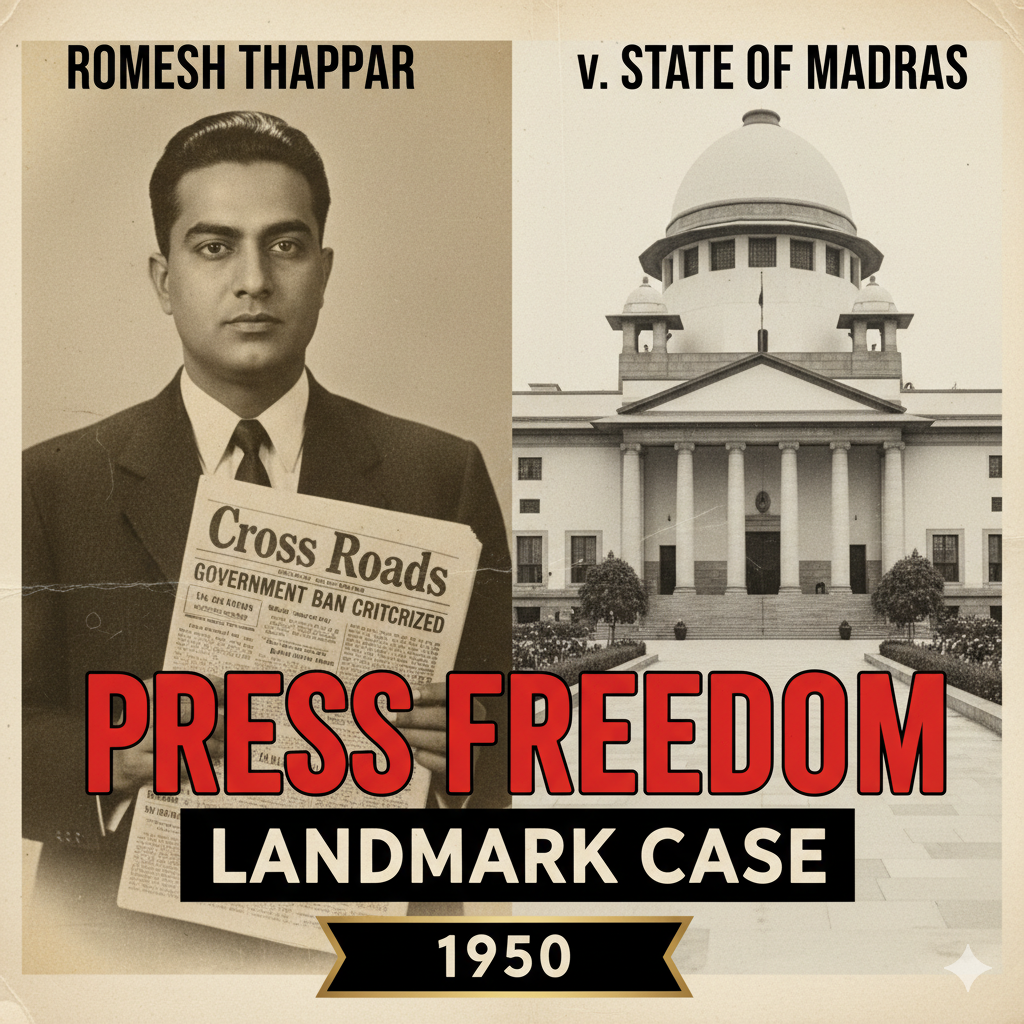

In the nascent years of the Republic of India, the Supreme Court delivered a judgment that would become a cornerstone of free speech and press freedom. Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras (1950) was not just a case; it was the first major test of the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression, and its outcome reverberates in our constitutional law to this day.

It was one of the very first cases where the Supreme Court struck down a law, declaring it unconstitutional for violating a fundamental right.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Factual Matrix: A Banned Journal

- Who: The petitioner was Romesh Thappar, the printer, publisher, and editor of a Bombay-based English weekly journal called “Cross Roads.”

- What: His journal was known for its leftist critique of the government’s policies.

- The Conflict: The Government of Madras, in March 1950, issued an order banning the entry and circulation of “Cross Roads” within the state.

- The Law Used: The government invoked Section 9(1-A) of the Madras Maintenance of Public Order Act, 1949. This law empowered the state government to prohibit the circulation of any document if it was satisfied that doing so was necessary for “public safety” or the “maintenance of public order.”

Angrieved by this executive ban, Romesh Thappar directly approached the Supreme Court of India. He filed a writ petition under Article 32 of the Constitution, arguing that the ban directly violated his fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression.

The Arguments Before the Court

The case presented a clear clash between individual liberty and state authority.

Arguments for the Petitioner (Romesh Thappar)

- Violation of Article 19(1)(a): Thappar’s primary contention was that the ban on his journal was a direct infringement of his fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression, which he argued also included the freedom to circulate his views.

- Act is Unconstitutional (Void): He argued that Section 9(1-A) of the Madras Act was unconstitutional and void under Article 13(1) (which voids all pre-Constitution laws inconsistent with Fundamental Rights).

- Restriction is Not Covered by Article 19(2): Thappar’s counsel argued that the grounds for the ban—”public safety” and “public order”—were not listed in Article 19(2), which (at the time) only permitted restrictions for “libel, slander, defamation, contempt of court or any matter which offends against decency or morality or which undermines the security of, or tends to overthrow, the State.” The vague term “public order” was not the same as the specific “security of the State.”

Arguments for the Respondent (State of Madras)

- Preliminary Objection (Procedural): The Advocate-General of Madras raised a preliminary objection, arguing that Thappar should have gone to the Madras High Court first under Article 226. They contended that since the High Court had concurrent jurisdiction, as a matter of “orderly procedure,” the petitioner should exhaust that remedy before approaching the Supreme Court directly.

- Substantive Argument (Defending the Law): The State argued that the terms “public safety” and “public order” in its Act were, in effect, synonymous with the “security of the State.” They contended that one could not exist without the other; widespread public disorder could easily threaten the very security of the state. Therefore, the law was a valid restriction under Article 19(2).

The Core Legal Questions

The arguments led to two critical questions for the Supreme Court:

- The Procedural Question: Could a person directly approach the Supreme Court under Article 32 without first going to the High Court under Article 226?

- The Substantive Question: Was the Madras Act, which allowed restrictions in the name of “public order,” a valid and constitutional restriction on the freedom of speech under Article 19(2) (as it existed in 1950)?

The Supreme Court’s Landmark Judgment

The Supreme Court, in a historic 5:1 majority decision, ruled in favor of Romesh Thappar and struck down the impugned law.

1. On Approaching the Supreme Court Directly (Article 32)

The Court firmly rejected the State’s preliminary objection. It held that the right to move the Supreme Court under Article 32 for the enforcement of fundamental rights is itself a guaranteed fundamental right. The Court declared itself the “protector and guarantor” of fundamental rights. Therefore, Romesh Thappar was well within his rights to approach the apex court directly.

2. On Freedom of Circulation

The Court emphatically ruled that freedom of speech and expression is not just about the right to publish one’s views. It held that:

”Freedom of speech and expression includes freedom of propagation of ideas, and that freedom is ensured by the freedom of circulation.”

Banning the circulation of a journal was, therefore, a direct and severe restriction on the freedom of speech itself.

3. “Public Order” vs. “Security of the State”

This was the most critical part of the judgment. The government had argued that “public order” was covered under “security of the State.”

The Supreme Court disagreed and drew a clear and vital distinction:

- Security of the State: This refers to very serious and aggravated forms of public disorder, such as rebellion, waging war against the state, or insurrection, which threaten to overthrow the state itself.

- Public Order: This is a much broader term. It can include minor, local breaches of the peace, like an affray or a riot, which do not threaten the foundations of the state.

The Court held that the original Constitution-makers had deliberately chosen the narrower term “security of the State” in Article 19(2). Since the Madras Act used the much wider and vaguer term “public order,” it gave the government sweeping powers to suppress any criticism or dissent, even if it didn’t threaten the state’s security.

Because the law was worded so broadly that it could be used for unconstitutional purposes (restricting speech for minor public order issues), the entire provision (Section 9(1-A)) was declared void and unconstitutional.

The Aftermath and Lasting Legacy

The Romesh Thappar judgment had an immediate and profound impact.

It sent a clear signal that the judiciary would not permit legislative or executive overreach when it came to fundamental rights. However, the government of the day, led by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, saw this judgment (and a similar one in Brij Bhushan v. State of Delhi) as a judicial obstacle.

This led directly to the First Constitutional Amendment in 1951. The amendment explicitly added “public order” and “incitement to an offence” as reasonable grounds for restricting the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression.

Despite the subsequent amendment, the Romesh Thappar case remains a foundational pillar of Indian constitutional law. It established that:

- Freedom of the press (including circulation) is an essential part of free speech.

- The Supreme Court is the ultimate guardian of fundamental rights.

- Any restriction on a fundamental right must be narrowly interpreted and must not be vague or overly broad.

It set the stage for a decades-long constitutional dialogue between the judiciary and the legislature on the precise contours of free speech in India.

- Dying declaration

- Bihar APO Exam Date 2026: Prelims Scheduled for July 15 – Check Official Notification

- UP APO Exam Date 2026 Announced: Check UPPSC Official Calendar & Schedule

- Indian Army JAG 124 Notification 2026: Vacancies, Eligibility, and Apply Online

- Official IBPS 2026-27 Calendar Out: Check SO Law & RRB Scale II Dates